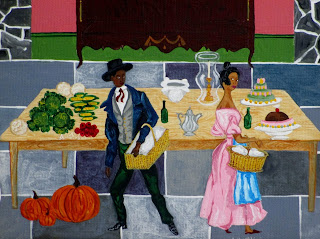

"Back from the French Market" by Andrew LaMar Hopkins 20 x 16

This is my last "Creole Kitchen painting titled "Back from the French Market" it was completed in October of 2015. Hours after it was completed the painting sold. The painting centers around two kitchen servants arriving back from the French Market. During the 19th century before refrigeration, Creoles bought fresh food daily. That food was prepared and consumed the same day. For over 200 years, the historic French Market has been an enduring symbol of pride and progress for the people of New Orleans. While the Market has existed on the same site since 1791

Coffee drinking played a central role in the life of the Market. According to one account written in 1859 “about midnight the market begins to show signs of life; the coffee tables are decorated with their array of cups of steaming Mocha” . . . 4 A British visitor to the city in the 1880′s wrote of the market: “They gave me deliciously aromatic coffee, dark . . . beautifully crystallized sugar, plenty of hot milk, the purest bread, the freshest of butter.” Chief features of the Market at this time included the Halle des Boucheries or Butcher’s Market, a fruit and vegetable market, a fish market, and grocery goods sold in the Market’s Red Stores.

Also in abundance were multitudes of flowers and fauna from throughout south Louisiana.

The painting in centered around a double arched Creole flagstone courtyard with formal French parterre and topiary garden. In between the two arched opening is a 18th century Louisiana inlay cabriole leg armoire. The flagstone tiled floor of the Creole kitchen would have been imported into Louisiana as Louisiana has no natural stone in the state. The large olive jar next to the cypress table on the floor is French provincial. On the cypress work table are french fruit, vegetables and desserts. Also on the table is a glass Hurricane globe with brass candlestick.

A early Louisiana Cypress work table

A 18th century Louisiana inlay cabriole leg armoire.

Copper pots and pans and molds have over a 18th century Louisiana cabriole leg drysink with sea sponge and porcelain pitcher. In the center of the copper is a 18th century French pottery water cistern.

French faïence water cisterns and covers with basins, 2nd half 18th century, painted with floral swags, scrolls and shell motifs.

Copper molds

Copper pots, pans and coffee pots

Copper pots and pans.

A Cypress cabinet holds Mochaware & Feather Edge Ware.

Mochaware is a soft pottery and much has been broken and can be found in privies all over New Orleans and Louisiana. It's also known as banded creamware or dipped ware. In general the term "mocha" is used to describe all dipped earthenwares.

Mocha decorated pottery is a type of dipped ware (slip-decorated, lathe-turned, utilitarian earthenware), mocha or mochaware, in addition to colored slip bands on white and buff-colored bodies, is adorned with dendritic (tree-like or branching) markings resembling the natural geological markings on moss agate, known as "mocha stone" in Great Britain in the late 18th century. The stone was imported from Arabia through the port of Mocha (al Mukha in Yemen) from whence came large supplies of coffee. An unknown potter or turner discovered that by dripping a colored acidic solution into wet alkaline slip on a pot body, the color would instantly ramify into the dendritic random markings that fit into the tradition of imitating geological surfaces prevalent in the potteries of that period. The earliest known dated example (1799) is a mug in the collection of the Christchurch Mansion Museum in Ipswich, England. Archival references are known that suggest production began as early as 1792.

Manufactured by potteries throughout Great Britain, France, and North America, mocha was the cheapest decorated ware available. Most British production went to export whereas France and North America manufactured for the home markets. Archaeological finds throughout the eastern United States suggest that mocha was used in taverns and homes, from lowly slave quarters to Thomas Jefferson's Monticello and Poplar Forest. After the mid 19th century, British imports waned, with those potteries still making mocha concentrating on government-stamped capacity-verified measures (jugs and mugs) for use in pubs and markets. North American product was based entirely on yellow or buff-colored bodies banded in black with broad white slip bands on which the dendritic markings appeared. Some British makers used yellow-firing clay, too, but the bulk of the wares were based on white bodies, the earliest being creamware and pearlware, while later, heavier and thicker bodies resembled ironstone, known best to archaeologists simply as "whiteware".

The simple design yet very elegant appeal - FeatherEdge stoneware/china - - dishes that are known as featheredge creamware pottery was produced by many 18th and 19th century pottery companies.

Feather Edge Ware, also known as Shell Edge Ware, (most collectors today use term featheredge), was used in the housholds of all classes for everyday use. It was made mainly in the Staffordshire and Leeds areas of England and exported to many areas of the world. The United States was the main importer. It was made with salt glaze stoneware, whiteware, pearlware, creamware and ironstone bodies. The older pieces have incised designs on the edge.

Feather Edge is a period term used by English potters and American importers for common 18th century creamware items having an embossed “comma-like” rim design. The term is specifically used in pattern books published by Wedgwood, Leeds, Castleford and the Don Pottery. It is most often found on plates and platters, but occasionally appears on hollowwares.

The painting centers around two kitchen servants arriving back from the French Market.

A Old Master copy of a painting of St. Veronica (or Berenice) is the woman of Jerusalem who wiped the face of Christ with a veil while he was on the way to Calvary. According to tradition, the cloth was imprinted with the image of Christ’s face.” Unfortunately, there is no historical evidence or scriptural reference to this event, but the legend of Veronica became one of the most popular in Christian lore and the veil one of the beloved relics in the Church

Saint Veronica by Guido Reni

Louisiana Slat-Back Side Chair. Turned Mulberry with Later Rush Seat. River Parishes Region, Louisiana. Circa Late-18th to Early-19th Centuries.

"Back from the French Market" by Andrew LaMar Hopkins 20 x 16

The first Creole kitchen painting was a commission from a friend and they have blossomed from since. I was a little hesitant to paint the first kitchen painting as I did not consider the kitchen a fine room of a house like my parlor or bedroom paintings. But once I started painting them. I have really got into the thyme, each new kitchen painting is better than the other. The kitchen is a room that just about everyone can relate too. 18th and 19th century kitchens were fascinating room filled with interesting cooking apparatus. If you would like to follow the progression of my artwork and these paintings please visit and like my facebook page

Here

.jpg)