Madonna and Child with Angels Giorgio di Tomaso Schiavone (Dalmatian, ca.

1433-1504) 1459-1460 (Renaissance)

In this altarpiece, the Virgin Mary wears gold brocade with pearls, and the

Christ Child, with his necklace of red coral, stands on a tasseled cushion.

Through these precious materials, the painter has communicated the divinity of

the figures. On the parapet at the bottom of the painting is a carnation. Its

Greek name, dianthus, means "flower of God." Schiavone was born in Dalmatia

(present-day Croatia) and immigrated to northern Italy, where he studied with

Francesco Squarcione of Padua. On the cartellino (little paper) in the

foreground, he proudly identifies himself as the disciple of this master. Like

his contemporaries, Schiavone was concerned with reviving the arts of antiquity,

as seen by the garlands at the top that imitate Roman sarcophagus reliefs. For

more information on this panel, please see Federico Zeri's 1976 catalogue no.

138, pp. 206-207.

The Walters Art Museum, located in Baltimore, Maryland's Mount Vernon

neighborhood, is a public art museum founded in 1934. The museum's collection

was amassed substantially by two men, William Thompson Walters (1819–1894), who

began serious collecting when he moved to Paris at the outbreak of the American

Civil War. His private collection became one of the largest and most valuable in

the United States. And his son Henry Walters (1848–1931), who refined the

collection and rehoused it in a palazzo building on Charles Street which opened

in 1909. Upon his death, Henry Walters bequeathed the collection of over 22,000

works and the original Charles Street palazzo building to the city of Baltimore,

“for the benefit of the public.” The collection touches masterworks of ancient

Egypt, Greek sculpture and Roman sarcophagi, medieval ivories, illuminated

manuscripts, Renaissance bronzes, Old Master and 19th-century paintings, Chinese

ceramics and bronzes, and Art Deco jewelry.

Scenes from the Life of Saint Catherine of Alexandria ca. 1430-1450

(Renaissance)

This three-part panel was originally part of a large altarpiece whose

central image probably represented Saint Catherine with the wheel of her

martyrdom. The left-hand panel depicts her vision of the Madonna and Child: the

Christ Child did not find Catherine worthy because she wasn't baptised and

refused to look at her. The middle scene illustrates her baptism. The right-hand

panel presents her second vision of the Madonna and Child: as a baptised

Christian she is now worthy in Christ's eyes and she is joined to him in a

mystic marriage. The delicate figures reflect the continuing influence of the

International Gothic style. Swabian painters of the following generation

developed a more harsly realistic style. Other fragments from the same

altarpiece are now in the Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt.

Adoration of the Three Kings by William Stetter (German, ca. 1490-1552)1526

(Early Modern)

The wise men who, according to the Gospels, came from the East to adore the

Christ Child and acknowledge his divinity, were often depicted as kings,

underscoring the importance of their homage. The star that they followed is in

the upper left corner. The oldest king, a regal European, kneels before the

Child and his mother. The middle-aged Turkish potentate, wearing a turban, looks

back through the doorway in the ruin where the holy family has taken refuge

toward the youngest ruler, a vigorous young African, attired in elegant

16th-century German fashion. His facial features are more individualized than

those of the other two, and it may be that he is based on a study made from

life. In the distance, some of the kings' followers ride horses with very long

necks, surely the artist's attempt at camels! The painter has created a kind of

stage set for his drama, using a perspective system made popular by his famous

fellow countryman Albrecht Dürer. The receding lines marked out in the masonry

go back, more or less, to one point, the hand of the man in the doorway (at

center).

Adoration of the Three Kings by William Stetter (German, ca. 1490-1552)1526

(Early Modern)

The wise men who, according to the Gospels, came from the East to adore the

Christ Child and acknowledge his divinity, were often depicted as kings,

underscoring the importance of their homage. The star that they followed is in

the upper left corner. The oldest king, a regal European, kneels before the

Child and his mother. The middle-aged Turkish potentate, wearing a turban, looks

back through the doorway in the ruin where the holy family has taken refuge

toward the youngest ruler, a vigorous young African, attired in elegant

16th-century German fashion. His facial features are more individualized than

those of the other two, and it may be that he is based on a study made from

life. In the distance, some of the kings' followers ride horses with very long

necks, surely the artist's attempt at camels! The painter has created a kind of

stage set for his drama, using a perspective system made popular by his famous

fellow countryman Albrecht Dürer. The receding lines marked out in the masonry

go back, more or less, to one point, the hand of the man in the doorway (at

center).

Virgin and Child Enthroned ca. 1515-1520 (Early Modern)

Here, Mary is both Queen of Heaven and a modest, pious mother, while

Christ's humanity is emphasized by his playfulness. The graceful but

conservative treatment of the Virgin reflects none of the new, 16th-century

emphasis on celebrating the human body seen in contemporary Italian painting.

However, the elaborate, fanciful architecture suggestive of a regal setting is

not the late Gothic style with pointed arches characteristic of Antwerp at that

time, but rather calls upon motifs from Roman architecture, such as the shell

motif behind the Virgin, then popular in Italy. Many paintings by this

outstanding but unidentified artist are known, but none are signed. He has long

been called the Master of Frankfurt, because there is a major painting of his in

Frankfurt, Germany. He recently has been identified as Hendrick van Wueluwe, who

was active in Antwerp from 1483 until his death in 1533. Though he was dean of

the painters' guild, there are no works documented by him.

Altarpiece with the Passion of Christ 1492-1495 (Late

Medieval-Renaissance)

The seven scenes of this Passion altarpiece are carved from separate blocks

of wood. They are: the Arrest of Christ, the Flagellation, Christ Carrying the

Cross, the Crucifixion (crucified figures and angels are later replacements),

Christ's Body Lowered from the Cross, the Entombment, and the Resurrection. Each

vignette is individually composed and originally was probably divided from the

next by slender columns at every third arch. We suggest this division by

inserting a painted backdrop to complement the remaining authentic architectural

detailing. To ensure that the drama of the Passion could be seen from a

distance, the artist made the figures animated, with large heads and exaggerated

gestures accentuated through color. He also raised the rear figures. The use of

wood allows the carving of weapons and other intricate details as stone would

not. In the 1490s, there were several workshops in Brussels producing large,

complex carved altarpieces, often for distant markets. The most famous shop was

that of Jan Borman, to which our altarpiece was once attributed. The Walters'

altarpiece was made for the Collegiate Church of Blainville-Crevon in Normandy,

in northwestern France. The altarpiece was damaged at some point in the past,

perhaps during the 16th century conflicts between Protestants and Catholics. The

Crucified Christ, the two thieves, and the attendant angels are 16th- or

17th-century replacements.

Altarpiece with the Passion of Christ 1492-1495 (Late

Medieval-Renaissance)

The seven scenes of this Passion altarpiece are carved from separate blocks

of wood. They are: the Arrest of Christ, the Flagellation, Christ Carrying the

Cross, the Crucifixion (crucified figures and angels are later replacements),

Christ's Body Lowered from the Cross, the Entombment, and the Resurrection. Each

vignette is individually composed and originally was probably divided from the

next by slender columns at every third arch. We suggest this division by

inserting a painted backdrop to complement the remaining authentic architectural

detailing. To ensure that the drama of the Passion could be seen from a

distance, the artist made the figures animated, with large heads and exaggerated

gestures accentuated through color. He also raised the rear figures. The use of

wood allows the carving of weapons and other intricate details as stone would

not. In the 1490s, there were several workshops in Brussels producing large,

complex carved altarpieces, often for distant markets. The most famous shop was

that of Jan Borman, to which our altarpiece was once attributed. The Walters'

altarpiece was made for the Collegiate Church of Blainville-Crevon in Normandy,

in northwestern France. The altarpiece was damaged at some point in the past,

perhaps during the 16th century conflicts between Protestants and Catholics. The

Crucified Christ, the two thieves, and the attendant angels are 16th- or

17th-century replacements.

Altarpiece with the Passion of Christ 1492-1495 (Late Medieval-Renaissance)

The seven scenes of this Passion altarpiece are carved from separate blocks of wood. They are: the Arrest of Christ, the Flagellation, Christ Carrying the Cross, the Crucifixion (crucified figures and angels are later replacements), Christ's Body Lowered from the Cross, the Entombment, and the Resurrection. Each vignette is individually composed and originally was probably divided from the next by slender columns at every third arch. We suggest this division by inserting a painted backdrop to complement the remaining authentic architectural detailing. To ensure that the drama of the Passion could be seen from a distance, the artist made the figures animated, with large heads and exaggerated gestures accentuated through color. He also raised the rear figures. The use of wood allows the carving of weapons and other intricate details as stone would not. In the 1490s, there were several workshops in Brussels producing large, complex carved altarpieces, often for distant markets. The most famous shop was that of Jan Borman, to which our altarpiece was once attributed. The Walters' altarpiece was made for the Collegiate Church of Blainville-Crevon in Normandy, in northwestern France. The altarpiece was damaged at some point in the past, perhaps during the 16th century conflicts between Protestants and Catholics. The Crucified Christ, the two thieves, and the attendant angels are 16th- or 17th-century replacements.

Altarpiece with the Passion of Christ 1492-1495 (Late

Medieval-Renaissance)

The seven scenes of this Passion altarpiece are carved from separate blocks

of wood. They are: the Arrest of Christ, the Flagellation, Christ Carrying the

Cross, the Crucifixion (crucified figures and angels are later replacements),

Christ's Body Lowered from the Cross, the Entombment, and the Resurrection. Each

vignette is individually composed and originally was probably divided from the

next by slender columns at every third arch. We suggest this division by

inserting a painted backdrop to complement the remaining authentic architectural

detailing. To ensure that the drama of the Passion could be seen from a

distance, the artist made the figures animated, with large heads and exaggerated

gestures accentuated through color. He also raised the rear figures. The use of

wood allows the carving of weapons and other intricate details as stone would

not. In the 1490s, there were several workshops in Brussels producing large,

complex carved altarpieces, often for distant markets. The most famous shop was

that of Jan Borman, to which our altarpiece was once attributed. The Walters'

altarpiece was made for the Collegiate Church of Blainville-Crevon in Normandy,

in northwestern France. The altarpiece was damaged at some point in the past,

perhaps during the 16th century conflicts between Protestants and Catholics. The

Crucified Christ, the two thieves, and the attendant angels are 16th- or

17th-century replacements.

Altarpiece with the Passion of Christ 1492-1495 (Late

Medieval-Renaissance)

The seven scenes of this Passion altarpiece are carved from separate blocks

of wood. They are: the Arrest of Christ, the Flagellation, Christ Carrying the

Cross, the Crucifixion (crucified figures and angels are later replacements),

Christ's Body Lowered from the Cross, the Entombment, and the Resurrection. Each

vignette is individually composed and originally was probably divided from the

next by slender columns at every third arch. We suggest this division by

inserting a painted backdrop to complement the remaining authentic architectural

detailing. To ensure that the drama of the Passion could be seen from a

distance, the artist made the figures animated, with large heads and exaggerated

gestures accentuated through color. He also raised the rear figures. The use of

wood allows the carving of weapons and other intricate details as stone would

not. In the 1490s, there were several workshops in Brussels producing large,

complex carved altarpieces, often for distant markets. The most famous shop was

that of Jan Borman, to which our altarpiece was once attributed. The Walters'

altarpiece was made for the Collegiate Church of Blainville-Crevon in Normandy,

in northwestern France. The altarpiece was damaged at some point in the past,

perhaps during the 16th century conflicts between Protestants and Catholics. The

Crucified Christ, the two thieves, and the attendant angels are 16th- or

17th-century replacements.

Altarpiece with the Passion of Christ 1492-1495 (Late

Medieval-Renaissance)

The seven scenes of this Passion altarpiece are carved from separate blocks

of wood. They are: the Arrest of Christ, the Flagellation, Christ Carrying the

Cross, the Crucifixion (crucified figures and angels are later replacements),

Christ's Body Lowered from the Cross, the Entombment, and the Resurrection. Each

vignette is individually composed and originally was probably divided from the

next by slender columns at every third arch. We suggest this division by

inserting a painted backdrop to complement the remaining authentic architectural

detailing. To ensure that the drama of the Passion could be seen from a

distance, the artist made the figures animated, with large heads and exaggerated

gestures accentuated through color. He also raised the rear figures. The use of

wood allows the carving of weapons and other intricate details as stone would

not. In the 1490s, there were several workshops in Brussels producing large,

complex carved altarpieces, often for distant markets. The most famous shop was

that of Jan Borman, to which our altarpiece was once attributed. The Walters'

altarpiece was made for the Collegiate Church of Blainville-Crevon in Normandy,

in northwestern France. The altarpiece was damaged at some point in the past,

perhaps during the 16th century conflicts between Protestants and Catholics. The

Crucified Christ, the two thieves, and the attendant angels are 16th- or

17th-century replacements.

Altarpiece with the Passion of Christ 1492-1495 (Late

Medieval-Renaissance)

The seven scenes of this Passion altarpiece are carved from separate blocks

of wood. They are: the Arrest of Christ, the Flagellation, Christ Carrying the

Cross, the Crucifixion (crucified figures and angels are later replacements),

Christ's Body Lowered from the Cross, the Entombment, and the Resurrection. Each

vignette is individually composed and originally was probably divided from the

next by slender columns at every third arch. We suggest this division by

inserting a painted backdrop to complement the remaining authentic architectural

detailing. To ensure that the drama of the Passion could be seen from a

distance, the artist made the figures animated, with large heads and exaggerated

gestures accentuated through color. He also raised the rear figures. The use of

wood allows the carving of weapons and other intricate details as stone would

not. In the 1490s, there were several workshops in Brussels producing large,

complex carved altarpieces, often for distant markets. The most famous shop was

that of Jan Borman, to which our altarpiece was once attributed. The Walters'

altarpiece was made for the Collegiate Church of Blainville-Crevon in Normandy,

in northwestern France. The altarpiece was damaged at some point in the past,

perhaps during the 16th century conflicts between Protestants and Catholics. The

Crucified Christ, the two thieves, and the attendant angels are 16th- or

17th-century replacements.

Altarpiece with the Passion of Christ 1492-1495 (Late

Medieval-Renaissance)

The seven scenes of this Passion altarpiece are carved from separate blocks

of wood. They are: the Arrest of Christ, the Flagellation, Christ Carrying the

Cross, the Crucifixion (crucified figures and angels are later replacements),

Christ's Body Lowered from the Cross, the Entombment, and the Resurrection. Each

vignette is individually composed and originally was probably divided from the

next by slender columns at every third arch. We suggest this division by

inserting a painted backdrop to complement the remaining authentic architectural

detailing. To ensure that the drama of the Passion could be seen from a

distance, the artist made the figures animated, with large heads and exaggerated

gestures accentuated through color. He also raised the rear figures. The use of

wood allows the carving of weapons and other intricate details as stone would

not. In the 1490s, there were several workshops in Brussels producing large,

complex carved altarpieces, often for distant markets. The most famous shop was

that of Jan Borman, to which our altarpiece was once attributed. The Walters'

altarpiece was made for the Collegiate Church of Blainville-Crevon in Normandy,

in northwestern France. The altarpiece was damaged at some point in the past,

perhaps during the 16th century conflicts between Protestants and Catholics. The

Crucified Christ, the two thieves, and the attendant angels are 16th- or

17th-century replacements.

Altarpiece with the Passion of Christ 1492-1495 (Late

Medieval-Renaissance)

The seven scenes of this Passion altarpiece are carved from separate blocks

of wood. They are: the Arrest of Christ, the Flagellation, Christ Carrying the

Cross, the Crucifixion (crucified figures and angels are later replacements),

Christ's Body Lowered from the Cross, the Entombment, and the Resurrection. Each

vignette is individually composed and originally was probably divided from the

next by slender columns at every third arch. We suggest this division by

inserting a painted backdrop to complement the remaining authentic architectural

detailing. To ensure that the drama of the Passion could be seen from a

distance, the artist made the figures animated, with large heads and exaggerated

gestures accentuated through color. He also raised the rear figures. The use of

wood allows the carving of weapons and other intricate details as stone would

not. In the 1490s, there were several workshops in Brussels producing large,

complex carved altarpieces, often for distant markets. The most famous shop was

that of Jan Borman, to which our altarpiece was once attributed. The Walters'

altarpiece was made for the Collegiate Church of Blainville-Crevon in Normandy,

in northwestern France. The altarpiece was damaged at some point in the past,

perhaps during the 16th century conflicts between Protestants and Catholics. The

Crucified Christ, the two thieves, and the attendant angels are 16th- or

17th-century replacements.

Altarpiece with the Passion of Christ 1492-1495 (Late

Medieval-Renaissance)

The seven scenes of this Passion altarpiece are carved from separate blocks

of wood. They are: the Arrest of Christ, the Flagellation, Christ Carrying the

Cross, the Crucifixion (crucified figures and angels are later replacements),

Christ's Body Lowered from the Cross, the Entombment, and the Resurrection. Each

vignette is individually composed and originally was probably divided from the

next by slender columns at every third arch. We suggest this division by

inserting a painted backdrop to complement the remaining authentic architectural

detailing. To ensure that the drama of the Passion could be seen from a

distance, the artist made the figures animated, with large heads and exaggerated

gestures accentuated through color. He also raised the rear figures. The use of

wood allows the carving of weapons and other intricate details as stone would

not. In the 1490s, there were several workshops in Brussels producing large,

complex carved altarpieces, often for distant markets. The most famous shop was

that of Jan Borman, to which our altarpiece was once attributed. The Walters'

altarpiece was made for the Collegiate Church of Blainville-Crevon in Normandy,

in northwestern France. The altarpiece was damaged at some point in the past,

perhaps during the 16th century conflicts between Protestants and Catholics. The

Crucified Christ, the two thieves, and the attendant angels are 16th- or

17th-century replacements.

Detail of Altarpiece with the Passion of Christ 1492-1495 (Late Medieval-Renaissance)

Detail of Altarpiece with the Passion of Christ 1492-1495 (Late Medieval-Renaissance)

Detail of Altarpiece with the Passion of Christ 1492-1495 (Late Medieval-Renaissance)

Detail of Altarpiece with the Passion of Christ 1492-1495 (Late Medieval-Renaissance)

Detail of Altarpiece with the Passion of Christ 1492-1495 (Late Medieval-Renaissance)

Detail of Altarpiece with the Passion of Christ 1492-1495 (Late Medieval-Renaissance)

Detail of Altarpiece with the Passion of Christ 1492-1495 (Late Medieval-Renaissance)

Detail of Altarpiece with the Passion of Christ 1492-1495 (Late Medieval-Renaissance)

Annunciation ca. 1515-1520 Jean Bellegambe (Netherlandish, ca.

1480-1534/1536)

The archangel Gabriel's greeting to the Virgin Mary and her response is

often represented on the exterior of winged altarpieces, as it signals Christ's

conception. Indeed, these two panels were originally the exterior wings of an

altarpiece featuring, on the interior, a Madonna and Child in the center (now in

Brussels) and Sts. Catherine and Barbara on the two side wings (Art Institute of

Chicago). While the interior was painted in naturalistic colors to create an

illusion of reality, the painter has followed a long tradition of painting the

exterior in "grisaille" (shades of gray) to resemble carved stone statues in a

niche. Jean Bellegambe's shop was in Douai, which was then near the border of

the Netherlands and France. While his patrons came mainly from northern France,

his style was deeply influenced by late medieval styles of Antwerp.

Saint Sebastian and a Bishop Saint Attributed to the Master of the Virgo inter Virgines (North Netherlandish, active ca. 1483-1498)1480-1495 (Early Modern)

The ethereal but naively drawn figures set against a landscape of flattened mounds are typical of the haunting compositions of this master, identified only through a group of works related to a painting of the Virgo inter Virgines (Virgin among Virgins) now in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. The small town of Delft, where woodcuts of his designs were published and where he is presumed to have worked, was far from the sophisticated cities to the south, such as Bruges and Ghent. Elongated panels, such as this one, typically functioned as the wings of an altarpiece. The presence of a coat of arms with the "fleur-de-lys" (lily) of France suggests that the altarpiece may have been commissioned for someone connected with the French royal court.

Saint Sebastian and a Bishop Saint Attributed to the Master of the Virgo

inter Virgines (North Netherlandish, active ca. 1483-1498)1480-1495 (Early

Modern)

The ethereal but naively drawn figures set against a landscape of flattened

mounds are typical of the haunting compositions of this master, identified only

through a group of works related to a painting of the Virgo inter Virgines

(Virgin among Virgins) now in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. The small town of

Delft, where woodcuts of his designs were published and where he is presumed to

have worked, was far from the sophisticated cities to the south, such as Bruges

and Ghent. Elongated panels, such as this one, typically functioned as the wings

of an altarpiece. The presence of a coat of arms with the "fleur-de-lys" (lily)

of France suggests that the altarpiece may have been commissioned for someone

connected with the French royal court.

Mummy Portrait of a Man late 1st century (Roman Imperial)

In Roman Egypt (30 BC-AD 324), artists adapted naturalistic painting styles to the ancient custom of making portrait masks for mummies. The portraits were often painted while the subject was in the prime of life and were hung in the home until the person's death. This practice continued in northern Egypt well into the Early Byzantine period.

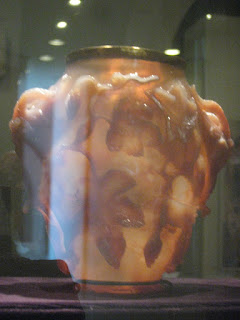

The "Rubens Vase" ca. 400 (Late Antique)

Carved in high relief from a single piece of agate, this extraordinary vase

was most likely created in an imperial workshop for a Byzantine emperor. It made

its way to France, probably carried off as treasure after the sack of

Constantinople in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade, where it passed through the

hands of some of the most renowned collectors of western Europe, including the

Dukes of Anjou and King Charles V of France. In 1619, the vase was purchased by

the great Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640). A drawing that he made

of it is now in Saint Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum, inv. 5430. The

subsequent fate of the vase before the 19th century is obscure. The gold mount

around its rim is struck with a French gold-standard mark used in 1809-1819 and

with the guarantee stamp of the French departement of Ain. A similar late Roman

agate vessel, the "Waddesdon Vase" or "Cellini Vase," in now in the British

Museum, London.

The "Rubens Vase" ca. 400 (Late Antique)

Carved in high relief from a single piece of agate, this extraordinary vase

was most likely created in an imperial workshop for a Byzantine emperor. It made

its way to France, probably carried off as treasure after the sack of

Constantinople in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade, where it passed through the

hands of some of the most renowned collectors of western Europe, including the

Dukes of Anjou and King Charles V of France. In 1619, the vase was purchased by

the great Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640). A drawing that he made

of it is now in Saint Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum, inv. 5430. The

subsequent fate of the vase before the 19th century is obscure. The gold mount

around its rim is struck with a French gold-standard mark used in 1809-1819 and

with the guarantee stamp of the French departement of Ain. A similar late Roman

agate vessel, the "Waddesdon Vase" or "Cellini Vase," in now in the British

Museum, London.

The "Rubens Vase" ca. 400 (Late Antique)

Carved in high relief from a single piece of agate, this extraordinary vase

was most likely created in an imperial workshop for a Byzantine emperor. It made

its way to France, probably carried off as treasure after the sack of

Constantinople in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade, where it passed through the

hands of some of the most renowned collectors of western Europe, including the

Dukes of Anjou and King Charles V of France. In 1619, the vase was purchased by

the great Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640). A drawing that he made

of it is now in Saint Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum, inv. 5430. The

subsequent fate of the vase before the 19th century is obscure. The gold mount

around its rim is struck with a French gold-standard mark used in 1809-1819 and

with the guarantee stamp of the French departement of Ain. A similar late Roman

agate vessel, the "Waddesdon Vase" or "Cellini Vase," in now in the British

Museum, London.

The "Rubens Vase" ca. 400 (Late Antique)

Carved in high relief from a single piece of agate, this extraordinary vase

was most likely created in an imperial workshop for a Byzantine emperor. It made

its way to France, probably carried off as treasure after the sack of

Constantinople in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade, where it passed through the

hands of some of the most renowned collectors of western Europe, including the

Dukes of Anjou and King Charles V of France. In 1619, the vase was purchased by

the great Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640). A drawing that he made

of it is now in Saint Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum, inv. 5430. The

subsequent fate of the vase before the 19th century is obscure. The gold mount

around its rim is struck with a French gold-standard mark used in 1809-1819 and

with the guarantee stamp of the French departement of Ain. A similar late Roman

agate vessel, the "Waddesdon Vase" or "Cellini Vase," in now in the British

Museum, London.

The "Rubens Vase" ca. 400 (Late Antique)

Carved in high relief from a single piece of agate, this extraordinary vase

was most likely created in an imperial workshop for a Byzantine emperor. It made

its way to France, probably carried off as treasure after the sack of

Constantinople in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade, where it passed through the

hands of some of the most renowned collectors of western Europe, including the

Dukes of Anjou and King Charles V of France. In 1619, the vase was purchased by

the great Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640). A drawing that he made

of it is now in Saint Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum, inv. 5430. The

subsequent fate of the vase before the 19th century is obscure. The gold mount

around its rim is struck with a French gold-standard mark used in 1809-1819 and

with the guarantee stamp of the French departement of Ain. A similar late Roman

agate vessel, the "Waddesdon Vase" or "Cellini Vase," in now in the British

Museum, London.

I feel like I can see the world or art, architecture and beauty through your blog. I have old china but use the new stuff when it is the public. If they break not such a bad thing, not that bad, but bad. Thanks, Richard from My Old Historic House.

ReplyDeleteHi Richard. Thank you for your kind comment. "He who seeks beauty shall find it." -Bill Cunningham. I know what you are talking about as far as fine crystal and china and the public.

ReplyDelete