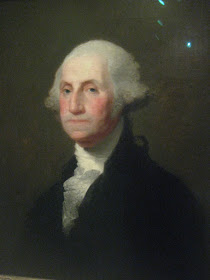

Portrait of George Washington ca, 1825 by Gilbert Stuart (American,

1755-1828)

In 1793, after working in London and Dublin for 18 years, Stuart returned

to America. Two years later, he painted his first portrait of George Washington,

showing the right side of the president's face, a format since known as the

Vaughan type. In the spring of 1796, Washington again sat for Stuart, and the

resulting portrait, which was never finished, was originally acquired by the

Boston Athenaeum. Depicting the left side of the face, this second version was

replicated many times, becoming an icon of American art. The Baltimore art

collector Robert Gilmor, Jr., for a fee of $150, commissioned the artist to

paint this example of the Athaeneum format. It was Stuart's last likeness of

Washington.

If you are ever in Baltimore Maryland. The Walters art museum should be top on

your list to see. It's FREE to visit the world class collections that I call a

mini Louvre. For five years I live two blocks away from this extraordinary

museum and visited often. The is the last post of a series of post of the

wonderful collections at the Walters. Next we will be visiting the collections

at the Baltimore Museum of Art. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres is one of my

favorite artist and the Walters has 4 of his paintings, the most you will see in

one place outside of France. My best friend has a Ingres in his private

collection. The photo's of this Walters series were taken in about a hour

just for you when I was in Baltimore last October for a good friends wedding,

enjoy.

The Walters Art Museum, located in Baltimore, Maryland's Mount Vernon

neighborhood, is a public art museum founded in 1934. The museum's collection

was amassed substantially by two men, William Thompson Walters (1819–1894), who

began serious collecting when he moved to Paris at the outbreak of the American

Civil War. His private collection became one of the largest and most valuable in

the United States. And his son Henry Walters (1848–1931), who refined the

collection and rehoused it in a palazzo building on Charles Street which opened

in 1909. Upon his death, Henry Walters bequeathed the collection of over 22,000

works and the original Charles Street palazzo building to the city of Baltimore,

“for the benefit of the public.” The collection touches masterworks of ancient

Egypt, Greek sculpture and Roman sarcophagi, medieval ivories, illuminated

manuscripts, Renaissance bronzes, Old Master and 19th-century paintings, Chinese

ceramics and bronzes, and Art Deco jewelry.

The Woman of Samaria (Rebecca ) 1859-1861 by William Henry Rinehart

(American, 1825-1874)

DThe Gospel of John relates the story of a Samaritan woman who is asked by

Jesus for a drink of water. After talking with him, she realizes that he is the

Messiah. Rinehart represents the woman, standing with her water vase. A native

of Maryland, the artist, with the financial help of William T. Walters, settled

in Rome in 1858. There, he sculpted idealized figures as well as portraits of

visiting Americans. He worked in a neoclassical style but was also influenced by

the emerging naturalistic trends in sculpture.

The Woman of Samaria (Rebecca ) 1859-1861 by William Henry Rinehart

(American, 1825-1874)

DThe Gospel of John relates the story of a Samaritan woman who is asked by

Jesus for a drink of water. After talking with him, she realizes that he is the

Messiah. Rinehart represents the woman, standing with her water vase. A native

of Maryland, the artist, with the financial help of William T. Walters, settled

in Rome in 1858. There, he sculpted idealized figures as well as portraits of

visiting Americans. He worked in a neoclassical style but was also influenced by

the emerging naturalistic trends in sculpture.

Bust of Mrs. William T. Waltersca, 1862 by William Henry Rinehart

(American, 1825-1874)

Ellen Harper (1822-62), the daughter of a prosperous Philadelphia merchant,

married William T. Walters in 1846. When she accompanied her husband on visits

to artists' studios, her genial personality contrasted with his gruff manner.

Ellen died of pneumonia after visiting the Crystal Palace in Sydenham in 1862.

This bust was finished after her death, and her friend Rinehart maintained that

producing it was the saddest duty he ever had to fulfill.

Portrait of Dr. Meer ca. 1795 by Rembrandt Peale (American,

1778-1860)

Rembrandt was the son of the well-known Neoclassical portraitist, Charles

Willson Peale, who used his influence to launch his children's careers as

artists. In 1795, Charles used his connections to get 17-year-old Rembrandt a

sitting with the growing American legend George Washington. Rembrandt would

later paint many portraits of Washington, as well as of Thomas Jefferson. The

younger Peale enjoyed a long, prosperous career, churning out likenesses of the

most distinguished members of Colonial America. Due to heavy demand, he often

relied on studio assistants. Consequently, the mature work can seem slightly

formulaic. However, this early work, probably done at about the same time that

the precocious young artist was introduced to Washington, has a refreshing

liveliness. The sitter, whose profession and identity remain somewhat unclear,

is captured as though directly engaging us. He points to a skull, which is

typically used in still-life painting as a symbol of human mortality. Scholars

have not yet determined if the prominent skull refers to the sitter's

professional status (a medical doctor?) or if it has some other, as yet

undeciphered symbolical role.

Portrait of George Washington ca, 1825 by Gilbert Stuart (American,

1755-1828)

In 1793, after working in London and Dublin for 18 years, Stuart returned

to America. Two years later, he painted his first portrait of George Washington,

showing the right side of the president's face, a format since known as the

Vaughan type. In the spring of 1796, Washington again sat for Stuart, and the

resulting portrait, which was never finished, was originally acquired by the

Boston Athenaeum. Depicting the left side of the face, this second version was

replicated many times, becoming an icon of American art. The Baltimore art

collector Robert Gilmor, Jr., for a fee of $150, commissioned the artist to

paint this example of the Athaeneum format. It was Stuart's last likeness of

Washington.

Portrait of Miss Moffat ca, 1826 by Sir Martin Archer Shee, P.R.A. (Irish,

1769-1850)

Shee, a fashionable portrait painter, chose his subjects from the worlds of

the theatre and high society. Although the sitter has not been identified, this

portrait was exhibited at the Royal Academy in London in 1826. Four years later,

Shee was elected president of the Academy. Miss Moffat is portrayed removing a

strand of pearls from a gold jewel box .

Bust of Dr. Dio Lewis ca, 1868 by Edmonia Lewis (American, 1845-after

1911)

Edmonia Lewis, the first African-American sculptor to receive national

recognition, was born in the village of Greenbush, near Albany, New York. Her

father was Haitian, and her mother was partly Native American, of the Chippewa

tribe, and partly African American. Lewis attended Oberlin College in Ohio and

in 1863 moved to Boston, where she received instruction from the sculptor Edward

Brackett. Two years later, she left the United States for Rome. She adopted the

prevailing neoclassical style of sculpture, as seen in this nude bust, but

softened it with a degree of naturalism, as reflected in the rendering of the

facial features. Most sculptors relied on the local craftsmen actually to carve

their works, but Lewis, sensitive to speculation that she was not responsible

for her sculptures, carved them personally. She had a successful career,

specializing in biblical subjects, themes recalling her Native American and

African ancestry, and portrait busts. Her sculpture "The Death of Cleopatra" was

favorably received when it was shown at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition

in 1876. Dioclesian Lewis (1823-1886) trained in medicine at Harvard College's

medical department and practiced briefly in Buffalo, New York. He is remembered

chiefly for lectures and publications dealing with preventive medicine and

physical hygiene, as well as for his support of liberal causes, including the

women's temperance movement. In 1865, he opened in Lexington, Massachusetts, the

Training School for Teachers of the New Gymnastics. His faculty members included

Theodore Dwight Weld, the noted abolitionist, and Catherine Beecher, sister of

Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of the novel that stirred abolitionist fervor,

Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852).

Portrait of Mrs. Decatur Howard Miller (Eliza Credilla Hare)ca, 1850 by

Alfred Jacob Miller (American, 1810-1874)

In this elegant, colorful portrait, a companion to Walters 37.2558, Miller

excels as a portraitist. He shows his sister-in-law standing with her back to a

mirror, which, in turn, reflects her bare neck and shoulders. Hanging from her

right shoulder is a red velvet drapery with a green lining. Beside her on a

table is a bowl containing a large goldfish. Mrs. Decatur H. Miller, née Eliza

Credilla Hare, was the daughter of Jesse Hare of Lynchburg, Virginia, and

Baltimore, and of Catherine Welch. Her father was an extremely wealthy tobacco

manufacturer who introduced the use of licorice in the manufacture of chewing

tobacco. Eliza was married to D. H. Miller on October 14, 1847.

Collision of Moorish Horsemen 1843-1844 Eugène Delacroix (French,

1798-1863)

Delacroix described the spectacular and violent military pageantry at the

court of Sultan Abd-er-Rahmen of Morocco (1778-1859), which he witnessed while

accompanying Count Charles de Mornay on a diplomatic expedition on behalf of

King Louis Philippe of France in 1832: "During their military exercises, which

consist of riding their horses at full-speed and stopping them suddenly after

firing a shot, it often happens that the horses carry away their riders and

fight each other when they collide."

The Christian Martyr 1853 Charles François Jalabert (French, 1819-1901)

(Artist) & Paul Delaroche (French, 1797-1856) (Artist)

Two Romans watch as a girl who has refused to sacrifice to pagan deities is

martyred by drowning. This copy of Delaroche's "Christian Martyr Drowned in the

Tiber during the Reign of Diocletian" (1853, now in the State Hermitage Museum,

St. Petersburg, Russia) was begun by Delaroche but completed by Jalabert, his

most devoted pupil. Such collaboration of student with master was a common

practice during the 19th century.

Oedipus and the Sphinx 1864 by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (French,

1780-1867)

The Sphinx, a mythical creature-part lion, part woman-grimaces in horror as

Oedipus solves her riddle: "What is that which has one voice and yet becomes

four-footed, two-footed, and three-footed?" Oedipus replies, "Man, for as a babe

he is four-footed, as an adult he is two-footed, and as an old man he gets a

third support, a cane," and the Sphinx hurls herself onto the rocks below, which

are strewn with the bones of her victims. Ingres, who frequently repeated the

subjects of his paintings, first depicted this story at the beginning of his

career and returned to it several times, making variations in the composition,

such as reversing the direction in which the figures faced.

Oedipus and the Sphinx 1864 by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (French,

1780-1867)

The Sphinx, a mythical creature-part lion, part woman-grimaces in horror as

Oedipus solves her riddle: "What is that which has one voice and yet becomes

four-footed, two-footed, and three-footed?" Oedipus replies, "Man, for as a babe

he is four-footed, as an adult he is two-footed, and as an old man he gets a

third support, a cane," and the Sphinx hurls herself onto the rocks below, which

are strewn with the bones of her victims. Ingres, who frequently repeated the

subjects of his paintings, first depicted this story at the beginning of his

career and returned to it several times, making variations in the composition,

such as reversing the direction in which the figures faced.

Oedipus and the Sphinx 1864 by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (French,

1780-1867)

The Sphinx, a mythical creature-part lion, part woman-grimaces in horror as

Oedipus solves her riddle: "What is that which has one voice and yet becomes

four-footed, two-footed, and three-footed?" Oedipus replies, "Man, for as a babe

he is four-footed, as an adult he is two-footed, and as an old man he gets a

third support, a cane," and the Sphinx hurls herself onto the rocks below, which

are strewn with the bones of her victims. Ingres, who frequently repeated the

subjects of his paintings, first depicted this story at the beginning of his

career and returned to it several times, making variations in the composition,

such as reversing the direction in which the figures faced.

Oedipus and the Sphinx 1864 by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (French,

1780-1867)

The Sphinx, a mythical creature-part lion, part woman-grimaces in horror as

Oedipus solves her riddle: "What is that which has one voice and yet becomes

four-footed, two-footed, and three-footed?" Oedipus replies, "Man, for as a babe

he is four-footed, as an adult he is two-footed, and as an old man he gets a

third support, a cane," and the Sphinx hurls herself onto the rocks below, which

are strewn with the bones of her victims. Ingres, who frequently repeated the

subjects of his paintings, first depicted this story at the beginning of his

career and returned to it several times, making variations in the composition,

such as reversing the direction in which the figures faced.

Reclining Venus 1822 by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (French,

1780-1867)

Ingres was deeply inspired by ancient Greek and Roman art as well by

Italian painting of the High Renaissance. Although he spent much of his career

in Rome, he resided in Florence from 1820 to 1824, where he painted this copy of

Titian's "Venus of Urbino" (1538), from the collection at the Pitti Palace. "The

Venus of Urbino" had inspired generations of artists. Ingres's version is the

same size as the original. He intended it to serve as a model for his close

friend, the sculptor Lorenzo Bartolini (1777-1850), who was creating a sculpture

based on the same subject.

The Betrothal of Raphael and the Niece of Cardinal Bibbiena 1813-14 by

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (French, 1780-1867)

Although he trained in the studio of the celebrated Neoclassical history

painter Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), Ingres defies easy classification. This

intimate painting reflects Ingres's Romantic fascination with the lives of

artists of the past whom he admired-in this case, Raphael. In this scene,

Cardinal Bibbiena presents his niece as a bride for Raphael, a demonstration of

the extraordinary esteem the cardinal felt for the handsome young artist. Ingres

was careful to use historical sources in his imaginative depiction of this

pivotal moment. Raphael's features are based on a portrait of a young man that

was once thought to be a self-portrait (National Gallery of Art, Washington,

D.C.); Bibbiena's likeness is based on a portrait by Raphael (Pitti Palace,

Florence); and the cardinal's niece was inspired by Sebastiano del Piombo's

image of a woman once identified as Raphael's mistress, called "La Fornarina"

(also in the Pitti Palace).

The Betrothal of Raphael and the Niece of Cardinal Bibbiena 1813-14 by

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (French, 1780-1867)

Although he trained in the studio of the celebrated Neoclassical history

painter Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), Ingres defies easy classification. This

intimate painting reflects Ingres's Romantic fascination with the lives of

artists of the past whom he admired-in this case, Raphael. In this scene,

Cardinal Bibbiena presents his niece as a bride for Raphael, a demonstration of

the extraordinary esteem the cardinal felt for the handsome young artist. Ingres

was careful to use historical sources in his imaginative depiction of this

pivotal moment. Raphael's features are based on a portrait of a young man that

was once thought to be a self-portrait (National Gallery of Art, Washington,

D.C.); Bibbiena's likeness is based on a portrait by Raphael (Pitti Palace,

Florence); and the cardinal's niece was inspired by Sebastiano del Piombo's

image of a woman once identified as Raphael's mistress, called "La Fornarina"

(also in the Pitti Palace).

Paris Kiosk 1880-1884 Jean Béraud (French, 1849-1935)

Like a number of other 19th-century artists, Béraud first trained to become

a lawyer before discovering his true calling. In 1872, he enrolled in the studio

of the portraiture specialist Léon Bonnat. While he began as a portraitist, he

eventually became known for his highly detailed scenes of urban life. Working

from a carriage that he converted into a mobile studio, Béraud recorded life on

the grand boulevards of Paris. The corner represented here can still be

recognized as the intersection of the Rue Scribe and the Boulevard des

Capucines. Like Degas, Béraud depicted modern life in all of its variety with

journalistic accuracy. Béraud, however, delighted in recording even the smallest

details, which are so precise that we can make out an advertisement for "Yedda,"

a popular ballet, and just below it, another playbill for a comic opera called

"La Fatinitza," which opened in Paris in 1879.

Art and Liberty 1859 by Louis Gallait (Belgian, 1810-1887)

This painting typifies the so-called "juste-milieu" (middle path) for which

Gallait was so admired during his lifetime. The subject is Romantic in its

idealization of the poor but virtuous itinerant musician, who bows to no

authority but his own artistic muse. At the same time, it is restrained in its

emotional tenor and painted with great technical assurance in the rendering of

the body and in the carefully described details of the musician's dress. This is

a reduced version of this subject now at the Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts of

Belgium. When the larger version was exhibited at the Salon of 1851, critics

praised the composition for its masterful drawing and melancholic dignity.

Italian Brigands Surprised by Papal Troops ca, 1831 Horace Vernet (French, 1789-1863)

In this scene, papal troops intercept brigands who are looting a coach and carrying off its passengers. During the 19th century, brigands, or "banditi," posed a real threat to travelers in rural areas of the Italian states, but they were also idealized as daring outlaws. Horace Vernet, the director of the Académie de France in Rome (1828-34) and professor at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris (1835-63), was regarded as a leader of the "juste-milieu," or the middle course between the opposing Romantic and Neoclassical factions in French painting. He chose dramatic, often contemporary, subjects but rendered them with the smooth brushwork and attention to detail associated with the Academic tradition.

At the Café ca, 1879 by Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883)

Manet was the quintessential "Painter of Modern Life," a phrase coined by

art critic and poet Charles Baudelaire. In 1878-79, he painted a number of

scenes set in the Cabaret de Reichshoffen on the Boulevard Rochechouart, where

women on the fringes of society freely intermingled with well-heeled gentlemen.

Here, Manet captures the kaleidoscopic pleasures of Parisian nightlife. The

figures are crowded into the compact space of the canvas, each one seemingly

oblivious of the others. When exhibited at La Vie Moderne gallery in 1880, this

work was praised by some for its unflinching realism and criticized by others

for its apparent crudeness.

Portrait of Estelle Balfour by 1863-1865 Edgar Degas (French,

1834-1917)

Estelle Musson Balfour (1843-1909), the artist's cousin from New Orleans,

visited France in 1863-65. She was in mourning for her husband, who had been

killed at the Battle of Corinth, Mississippi, while fighting on the side of the

Confederacy in the Civil War. At the time that this portrait was painted, Mrs.

Balfour was going blind. Degas, too, would eventually lose his sight, and this

painting explores the experience of seeing those who cannot see.

Springtime 1872 by Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

Monet moved to Argenteuil, a suburban town on the right bank of the Seine

River northwest of Paris, in late December 1871. Many of the types of scenes

that he and the other Impressionists favored could be found in this small town,

conveniently connected by rail to nearby Paris. In this painting, Monet was less

interested in capturing a likeness than in studying how unblended dabs of color

could suggest the effect of brilliant sunlight filtered through leaves. During

the early 1870s, Monet frequently depicted views of his backyard garden that

included his wife, Camille, and their son, Jean. However, when exhibited at the

Second Impressionist Exhibition in 1876, this painting was titled more

generically, "Woman Reading.

Still Life ca 1859 by Johann Wilhelm Preyer (German, 1803-1889)

On a table covered with a red cloth are a slender glass of sparkling wine,

a silver salver bearing oysters, a slice of lemon, a bunch of purple grapes

still attached to a sprig of vine with one large leaf, and several almonds. A

housefly is perched on the stem of the vine.

Portrait of Napoleon III ca, 1868 by Adolphe Yvon (French, 1817-1893)

Yvon served as the principal battle-painter of France's Second Empire

(1852-70), executing a number of monumental canvases for the palace at

Versailles. The French emperor is shown in his prime, two years before the

defeat of his forces in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871).

Circular Medallion ca, 1805 by Piat Joseph Sauvage (Flemish, 1744-1818)

On this medallion, Napoleon is idealized as a Roman emperor crowned with a

laurel wreath. He is identified as the French emperor (r. 1804-14 and 1815) and

as king of Italy (r. 1805-14). Sauvage, who left his native Antwerp for Paris in

1774, became famous for painting porcelain to resemble marble.

The Waning Honeymoon 1878 by George Henry Boughton (American,

1833-1905)

Boughton was the son of a Norwich farmer who was taken to America while

still an infant. He initially opened a studio in Albany, New York, listing

himself as a landscape painter. He eventually settled in London where he

produced historical genre scenes, many of which were set in New England. In this

autumnal scene of the English Regency, a young couple is seated at the fork of

diverging paths, an ominous sign for their future.

The Blind Beggar ca, 1856 by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, R.A., O.M.

(Anglo-Dutch, 1836-1912)

Bathed in sunlight, an attractive young woman in Dutch country dress leans

from an open window in one corner of a vine-covered cottage. She reaches out to

drop coins in the hat of a young man outiside her window, who is wearing a

patched and dirty tunic. He is soliciting charity on behalf of an elderly woman,

who waits beside him in a wheeled, hand-drawn conveyance. A glimpse of a distant

landscape is visible over the brick wall to the right. Although Alma-Tadema was

only 20 when he painted this scene, he already shows in it the narrative skills

that will bring him such success with his later re-creations of life in Greek

and Roman antiquity. This genre scene was the artist's first major

commission.

The Blind Beggar ca, 1856 by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, R.A., O.M.

(Anglo-Dutch, 1836-1912)

Bathed in sunlight, an attractive young woman in Dutch country dress leans

from an open window in one corner of a vine-covered cottage. She reaches out to

drop coins in the hat of a young man outiside her window, who is wearing a

patched and dirty tunic. He is soliciting charity on behalf of an elderly woman,

who waits beside him in a wheeled, hand-drawn conveyance. A glimpse of a distant

landscape is visible over the brick wall to the right. Although Alma-Tadema was

only 20 when he painted this scene, he already shows in it the narrative skills

that will bring him such success with his later re-creations of life in Greek

and Roman antiquity. This genre scene was the artist's first major

commission.

Diogenes ca, 1860 by Jean-Léon Gérôme (French, 1824-1904)

The Greek philosopher Diogenes (404-323 BC) is seated in his abode, the

earthenware tub, in the Metroon, Athens, lighting the lamp in daylight with

which he was to search for an honest man. His companions were dogs that also

served as emblems of his "Cynic" (Greek: "kynikos," dog-like) philosophy, which

emphasized an austere existence. Three years after this painting was first

exhibited, Gerome was appointed a professor of painting at the Ecole des

Beaux-Arts where he would instruct many students, both French and foreign.

Princess Kotschoubey 1860 by Franz Xaver Winterhalter (German, 1805-1875)

Although born a peasant in the Black Forest region of southwestern Germany,

Winterhalter became the foremost portraitist of European royalty and nobility.

Hélène Bibikoff was initially married to Prince Esper A. Belosselsky-Belozersky

and subsequently to Prince Kotschoubey, the son of the chancellor of the Russian

empire. A woman of great wealth, even by the standards of her time, the Princess

travelled extensively, mingling in the European courts, and entertaining

lavishly. Her palace on the Nevsky Prospekt, St. Petersburg, was the setting for

balls that rivaled those of the court in all its grandeur. She is reported to

have maintained her role as a social leader at the imperial court with

autocratic zeal. Winterhalter has depicted her in one of his customary formats,

three-quarter length, nearly life-size, and painted against an overcast sky. She

wears a black silk gown, black lace, and jewelry, including a necklace of large

pearls, a pearl brooch with a large pendant pearl, a flexible, serpentine

bracelet, and several rings.

Othello by William Mulready 1840-1863 (British, 1786-1863) (?)

Mulready spent most of his career in London painting genre subjects. Many

of his major works are now on display in the Victoria and Albert Museum. Here,

he has portrayed the African-American actor Ira Aldridge (1805 (?)-1867), who

won renown in Europe for his Shakespearean roles, including Othello, Lear, and

Macbeth. This half-length portrait shows Aldrige in battle armor, with a flag at

his right, in front of a stone archway.

The Scarlet Letter 1861 by Hugues Merle (French, 1823-1881)

Nathaniel Hawthorne, author of "The Scarlet Letter" (1850), regarded this

painting, which William Walters commissioned from Merle in 1859, as the finest

illustration of his novel. Set in Puritan Boston, the novel relates how Hester

Prynne was publicly disgraced and condemned to wear a scarlet letter "A" for

adultery. Arthur Dimmesdale, the minister who fathered her child, and Roger

Chillingworth, Hester's elderly husband, appear in the background. Merle's

canvas reflects some of the same 19th-century historical interest in the

Puritans as Hawthorne's book, a fascination that reached its peak with the

establishment of Thanksgiving as a national holiday in 1863. By depicting Hester

and her daughter, Pearl, in a pose that recalls that of the Madonna and Child,

Merle underlines "The Scarlet Letter"'s themes of sin and redemption.

Odalisque with Slave 1842 by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (French,

1780-1867)

An odalisque (female member of a harem) reclines exposed in the harem

listening to a servant's lute music. This painting was commissioned by King

Wilhelm I of Württemberg and was executed by Ingres with the assistance of his

pupil Paul Flandrin. A version of this subject painted three years earlier shows

the odalisque in an enclosed room rather than with the garden vista in the

background (Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts). This exotic composition,

which was inspired by a passage from Lady Mary Wortley Montagu's Turkish Letters

(1763), may have been conceived by Ingres in response to his rival Eugène

Delacroix's success as a painter of Near Eastern subjects.

Saïd Abdullah of the Mayac, Kingdom of the Darfur (Sudan) 1848 by

Charles-Henri-Joseph Cordier (French, 1827-1905)

Cordier submitted a plaster cast of the bust of an African visitor to Paris

to the Salon of 1848, and two years later he again entered it as a bronze. A

young African woman served as the model for the companion piece in 1851 (Walters

54.2665). Regarded by 19th-century viewers as powerful expressions of nobility

and dignity in the face of grave injustice, these sculptures proved to be highly

popular: casts were acquired by the Museum of National History in Paris and also

by Queen Victoria. The Walters' pair were cast by the Paris foundry Eck and

Durand in 1852.

African Venus ca, 1851 by Charles-Henri-Joseph Cordier (French, 1827-1905)

Cordier submitted a plaster cast of the bust of an African visitor to Paris

to the Salon of 1848, and two years later he again entered it as a bronze

(Walters 54.2664). A young African woman served as the model for this companion

piece in 1851. Regarded as powerful expressions of nobility and dignity, these

sculptures proved to be highly popular: casts were acquired by the Museum of

National History in Paris and also by Queen Victoria. The Walters' pair were

cast by the Paris foundry Eck and Durand in 1852. These bronzes were esteemed by

19th-century viewers as expressions of human pride and dignity in the face of

grave injustice.

Odalisque with Slave 1842 by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (French,

1780-1867)

An odalisque (female member of a harem) reclines exposed in the harem

listening to a servant's lute music. This painting was commissioned by King

Wilhelm I of Württemberg and was executed by Ingres with the assistance of his

pupil Paul Flandrin. A version of this subject painted three years earlier shows

the odalisque in an enclosed room rather than with the garden vista in the

background (Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts). This exotic composition,

which was inspired by a passage from Lady Mary Wortley Montagu's Turkish Letters

(1763), may have been conceived by Ingres in response to his rival Eugène

Delacroix's success as a painter of Near Eastern subjects.

African Venus ca, 1851 by Charles-Henri-Joseph Cordier (French, 1827-1905)

Cordier submitted a plaster cast of the bust of an African visitor to Paris

to the Salon of 1848, and two years later he again entered it as a bronze

(Walters 54.2664). A young African woman served as the model for this companion

piece in 1851. Regarded as powerful expressions of nobility and dignity, these

sculptures proved to be highly popular: casts were acquired by the Museum of

National History in Paris and also by Queen Victoria. The Walters' pair were

cast by the Paris foundry Eck and Durand in 1852. These bronzes were esteemed by

19th-century viewers as expressions of human pride and dignity in the face of

grave injustice.

The Scarlet Letter 1861 by Hugues Merle (French, 1823-1881)

Nathaniel Hawthorne, author of "The Scarlet Letter" (1850), regarded this

painting, which William Walters commissioned from Merle in 1859, as the finest

illustration of his novel. Set in Puritan Boston, the novel relates how Hester

Prynne was publicly disgraced and condemned to wear a scarlet letter "A" for

adultery. Arthur Dimmesdale, the minister who fathered her child, and Roger

Chillingworth, Hester's elderly husband, appear in the background. Merle's

canvas reflects some of the same 19th-century historical interest in the

Puritans as Hawthorne's book, a fascination that reached its peak with the

establishment of Thanksgiving as a national holiday in 1863. By depicting Hester

and her daughter, Pearl, in a pose that recalls that of the Madonna and Child,

Merle underlines "The Scarlet Letter"'s themes of sin and redemption.