Antinous and Hadrian

Hadrian

Publius Aelius Hadrianus (24 January 76 – 10 July 138), commonly known as Hadrian and after his apotheosis Divus Hadrianus, was Roman Emperor from 117 to 138. He is best-known for building Hadrian's Wall, which marked the northern limit of Roman territory in Britain. In Rome, he built the Pantheon and the Temple of Venus and Roma. In addition to being emperor, Hadrian was a humanist and was philhellene in all his tastes. He was the third of the so-called Five Good Emperors.

Hadrian was born Publius Aelius Hadrianus to a ethnically Italian family in Italica near Seville. Hadrian's parents died in 86 when Hadrian was ten, the boy then became a ward of both his father's cousin Trajan who became Emperor in 98 CE and his father's dear friend Publius Acilius Attianus (who was later Trajan’s Praetorian Prefect). The relationship between Hadrian and Trajan is open to speculation. It seemed to vary between immense affection to near hatred. Since it is often said that the only thing that the two truly had in common was a love of boys, it is possible though not proven that they were in fact lovers, and it has long been alleged that many of the troubles between the two were caused by the boys they kept. Hadrian was schooled in various subjects particular to young Roman aristocrats of the day, and was so fond of learning Greek literature that he was nicknamed Graeculus ("Greekling"). His predecessor Trajan was a maternal cousin of Hadrian's father. Trajan never officially designated an heir, but according to his wife Pompeia Plotina, Trajan named Hadrian emperor immediately before his death. Trajan's wife and his friend Licinius Sura were well-disposed towards Hadrian, and he may well have owed his succession to them.

In the year 100 CE, two years after his guardian became Emperor, Hadrian was wed to the young great-niece of said guardian. The girl, Sabina, was approximately 13 and still fairly young even by Roman terms of marriage. There was never to be much fondness between Sabina and Hadrian, and indeed there was much hostility between the two, who were married for purely political reasons as Sabina was the Emperor's closest unmarried female relative. In retaliation to the lack of emotion given her by her husband, Sabina apparently took steps to insure that Hadrian would never have a child by her. To describe his wife, Hadrian used the words, "moody and difficult," and declared that if he were a private citizen free to do his own will, he would divorce her. There was also rumors that he tried to poison her.

During his reign, Hadrian traveled to nearly every province of the empire. An ardent admirer of Greece, Hadrian sought to make Athens the cultural capital of the empire and ordered the construction of many opulent temples in the city. It is believe he met a Greek boy named Antinous who became his lover and was to underline his philhellenism and led to the creation of one of the most popular cults of ancient times. the boy was thirteen or fourteen at the time they met. Statues of a young Antious from around this age survive

Antinous depicted as the Egyptian god Osiris, originally discovered in 1738-9 in Hadrian's Villa. From the Vatican Museum collection, Museo Gregoriano Egizio 22795, seen here while at the British Museum as part of the "Hadrian: Empire and Conflict" exhibition.

Antinous

Antinous was born in the town of Bithynion-Claudiopolis, in the Greek province of Bithynia on the northwest coast of Asia Minor in what is now north-west Turkey. His birth was definitely in November and most probably on the 27th. The year of his birth is not known, but at the time of his death in 132, he was described as "ephebe" and "meirkakion," two words meant to convey a boy is his late teens or a young man of around twenty. From this we can postulate that Antinous was born in either 110, 111, or 112. His parentage is unknown, as no details of his family have remained extant. It is thought that his parents may have originally been mentioned in the epitaph on the obelisk that Hadrian erected for the boy after his death, but the section where such mention is thought to have been contained is agonizingly chipped off the stone.

Little is known as to how Antinous came to be in the house of Hadrian. It is thought that he was taken from Claudiopolis during one of Hadrian's tours of the provinces in 123, when the boy was around eleven or twelve. Whether he was taken by force or went willingly is open to speculation, but that he later became the Emperor's favorite seems to preclude his ever being a slave since Hadrian was known to accept social boundaries. The fact that many busts where made of an Antinous aged around thirteen would indicate that he was a member of the Emperor's circle soon after leaving his home. It is thought that he was taken to Rome as a page and perhaps entered into the imperial paedagogium. The paedagogium may have, in part, served as a harem of boys, but its official role was that of a polishing school designed to train the boys to become palace or civil servants. It is impossible to say exactly when Hadrian became enamored of Antinous but it is thought to have been sometime between the Emperor's return to Italy in 125 and his next trip to Greece in 128, on which tour Antinous accompanied him as favorite.

Antinous as a priest of the imperial cult (Louvre)

The relationship between Hadrian and Antinous would be looked down on today but in ancient Greece and Roman Empire Pederasty or paederasty ( /ˈpɛdəræsti/, UK /ˈpiːdəræsti/) a sexual relationship between an older man and an adolescent boy outside his immediate family was common and excepted part of ancient society. The word pederasty derives from Greek (paiderastia) "love of children" or "love of boys", Historically, pederasty has existed as a variety of customs and practices within different cultures. The status of pederasty has changed over the course of history, at times considered an ideal and at other times a crime.

While relationships in ancient Greece involved boys from 12 to about 17 or 18 (Cantarella, 1992), in Renaissance Italy, the boys were typically between 14 and 19, In antiquity, pederasty was seen as an educational institution for the inculcation of moral and cultural values by the older man to the younger, as well as a form of sexual expression. It entered representation in history from the Archaic period onwards in Ancient Greece, According to Plato, in ancient Greece, pederasty was a relationship and bond – whether sexual or chaste – between an adult man and an adolescent boy outside his immediate family. While most Greek men engaged in sexual relations with both women and boys, exceptions to the rule were known, some avoiding relations with women, and others rejecting relations with boys. In Rome, relations with boys took a more informal and less civic path, with older men either taking advantage of dominant social status to extract sexual favors from their social inferiors, or carrying on illicit relationships with freeborn boys.

Capitoline Antinous, Capitoline Museums, from the Villa Adriana

That spiritual love should also have a physical component was seen as obvious and proper in most circles and hence few thought anything at all wrong or even odd about the system of pederasty. In deed, so much poetry and art was dedicated to it that even men who never took eromenoi and who seemed to have actually preferred the attentions of a woman often wrote verses praising boys anyway, just so that they would be accepted by their peers.

The Antinous Braschi type (Louvre)

While touring Egypt in 130, Antinous mysteriously drowned in the Nile. In October 130, according to Hadrian, cited by Dio Cassius, "Antinous was drowned in the Nilus". (D.C. 69.11) It is not known for certain whether his death was the result of accident, suicide, murder, or (voluntary) religious sacrifice, Deeply saddened, Hadrian founded the Egyptian city of Antinopolis, and had Antinous deified – an unprecedented honour for one not of the ruling family. The cult of Antinous became the most popular of all cults in the Greek-speaking world. At Antinous's death the emperor decreed his deification, and the 2nd century Christian writer Tatian mentions a belief that his likeness was placed over the face of the Moon, though this may be exaggerated due to his anti-pagan polemical style.

The grief of the emperor knew no bounds, causing the most extravagant veneration to be paid to his memory. Cities were founded in his name, medals struck with his effigy, and statues erected to him in all parts of the empire. Following the example of Alexander (who sought divine honors for his beloved general, Hephaistion, when he died) Hadrian had Antinous proclaimed a god. Temples were built for his worship in Bithynia, Mantineia in Arcadia, and Athens, festivals celebrated in his honor and oracles delivered in his name. The city of Antinopolis or Antinoe was founded on the site of Hir-wer where he died (Dio Cassius lix.11; Spartianus, "Hadrian"). One of Hadrian's attempts at extravagant remembrance failed, when the proposal to create a constellation of Antinous being lifted to heaven by an eagle (the constellation Aquila) failed of adoption.

After deification, Antinous was associated with and depicted as the Ancient Egyptian god Osiris, associated with the rebirth of the Nile. Antinous was also depicted as the Roman Bacchus, a god related to fertility, cutting vine leaves. Antinous's was the only non-imperial head ever to appear on the coinage.

Rome, Museo Capitolino, Galleria, N° MC0294, exhibited. Acquired in December 1733 from the Cardinal Albani, and exhibited uninterruptedly in the Galleria since 1734.

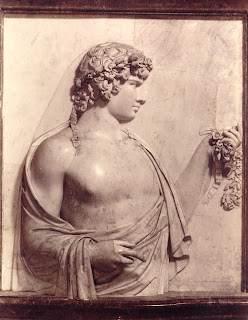

Antinous As Bacchus

The cult of Antinous was severely condemned by the emerging Catholic Church. It was seen as both a blasphemy and a celebration of an immoral sexual relationship. A flavour of this condemnation is caught in some lines from the early Christian poet, Prudentius : Ironically over the century's Pop's have collected some of the finest statues of Antinous are own by the Catholic Church located in the Vatican museum.

Vatican Museums, colossal bust, from Villa Adriana

Cassius Dio (c.164-post 229) (The section of his Roman History covering Hadrian's reign is known only from the 11th century epitome by Xiphilinus) 69.11.2-4:

"Antinous was from Bithynium, a Bithynian city which we also call Claudiopolis, and he had become Hadrian's boy-favourite (paidika); and he died in Egypt, either by falling into the Nile, as Hadrian writes [lost], or, as the truth is, having been offered in sacrifice (hierourgethesis). For Hadrian was in any case, as I have said, very keen on the curious arts, and made use of divinations and incantations of all kinds. Thus Hadrian honoured Antinous - either on account of his love for him, or because the youth had voluntarily undertaken to die for him (ethelontes ethanatothe) (for there was need for a life to be surrendered willingly, to achieve what Hadrian intended [¶]), by founding a city on the spot where he suffered this fate and naming it after him [Antinoöpolis; modern El Sheik'ibada]. He also set up statues of him, or rather sacred images, practically all over the world. Finally he declared that he had seen a star, which he took to be that of Antinous, and gladly listened to the fictitious tales spun by his companions, to the effect that the star had really come into being from the soul of Antinous and had then appeared for the first time. As a result of this, indeed, he was ridiculed, especially because when his sister Paulina died he had not immediately accorded her any honours."

¶ As in the soteriological Greek myth (recorded by Appollodorus, et al.) of Alcestis, wife of Admetus, king of Thrace, who was prepared to die in place of her husband, but was returned to earth by Persephone.

Antinous bust of the Prado museum, Royal collection, Madrid

Aurelius Victor (fl. 361-389) De Caesaribus (c.360) 14.5-7:

"As a result of Hadrian's devotion to luxury and lasciviousness (luxus lasciviaeque), hostile rumours arose about his debauching of young men (stupra puberibus) and his burning passion for his notorious attendant Antinous (Antinoi flagravisse famoso ministerio); and that it was for no other reason that a city was founded named after Antinous, or that Hadrian set up statues of the ephebe. Some indeed maintain that this was done because of piety or religion (pia reliogiosaque): the reason being, they say, that Hadrian wanted to extend his own life-span by any means, and when the magicians demanded a volunteer to substitute for him, everyone declined, but Antinous offered himself - hence the aforementioned honours done to him. We will leave the matter undecided although, in the case of an indulgent nature (remissum ingenium), we regard as suspicious (suspectum) the association between persons of disparate age (aestimantes societatem aevi longe imparilis)."

Antinous allegorically as Ganymede offering ambrosia to Jupiter (or Hadrian).

Scriptores) Historia Augusta (SHA) (c.395 based on earlier sources) Hadr. 14.5-7:

"While sailing on the Nile he [Hadrian] lost his [¶] Antinous, for whom he wept like a woman. (Antinoum suum, dum per Nilum navigat, quem muliebriter flevit) There are various rumours about this person, some asserting that he offered himself as a sacrifice on behalf of Hadrian, others - what both his beauty and Hadrian's excessive pleasure-seeking suggest. (de quo varia fama est, aliis eum devotum pro Hadriano adserentibus, aliis quod et forma eius ostentat et nimia voluptas Hadriani) At any rate, the Greeks, at Hadrian's wish, consecrated him as a god, claiming that oracles were given through him, which Hadrian is supposed to have composed himself." ¶ Possibly an adjective has been lost here.

As Bacchus, Vatican

Justin Martyr (c.100-c.165):

Apologia (c.150) I:XXIX - "Antinous, who was alive but lately, and whom all were prompt, through fear, to worship as a god, though they knew both who he was and what was his origin."

As Bacchus, Vatican

Protrepticus (Exhortation to the Greeks) (c.190) IV - "Another new deity was added to the number with great religious pomp in Egypt, and was near being so in Greece by the king of the Romans [Hadrian], who deified Antinous [in 130CE], whom he loved as Zeus loved Ganymede, and whose beauty was of a very rare order: for lust is not easily restrained, destitute as it is of fear; and men now observe the sacred nights of Antinous, the shameful character of which the lover who spent them with him knew well. Why reckon him among the gods, who is honoured on account of uncleanness? And why do you command him to be lamented as a son? And why should you enlarge on his beauty? Beauty blighted by vice is loathsome. Do not play the tyrant, O man, over beauty, nor offer foul insult to youth in its bloom. Keep beauty pure, that it may be truly fair. Be king over beauty, not its tyrant. Remain free, and then I shall acknowledge thy beauty, because thou hast kept its image pure: then will I worship that true beauty which is the archetype of all who are beautiful. There is a tomb of the beloved boy (eromenos). A temple of this Antinous and a city [Antinoöpolis]. For just as temples are held in reverence, so also are sepulchres, and pyramids, and mausoleums, and labyrinths, which are temples of the dead, as the others are sepulchres of the gods. As teacher on this point, I shall produce to you the Sibyl prophetess:- 'Not the oracular lie of Phoebus, Whom silly men called God, and falsely termed Prophet; But the oracles of the great God, who was not made by men's hands, Like dumb idols of Sculptured stone.' "

Antinoopolis, fragment of a white marble statue of Antinous. Found during the “Expédition d’Egypte” (1799-1801) and transported to Cairo, where it got lost. Innumerable fragments of similar statues, mutilated on obvious purpose, were at that time still laying at the foot of the columns erected on both sides of the main street of Antinoopolis. In the mid-19th century, any bit and piece of marble was converted into lime to construct a factory in Rhoda, on the other edge of the Nile. As a result, Antinoopolis disappeared from the surface of the earth. «Les formes pures et juvéniles respirent pourtant une certaine vigueur ; autant qu’on puisse en juger, l’attitude était d’une mollesse pleine de grâce» (Edmé-François Jomard, 1818)

The Belvedere Antinous St Petersburg, Peterhof. The original statuary decoration of the Grand Cascade, conceived in the 1730’s, gave way in 1800-1801 to copies of classical statues. Many artists contributed. This gilded bronze is by the master founder Vasily Petrovich Ekimov (1758-1837). During WWII, Peterhof was severely damaged and most of today's statues are modern restorations.

Antinous-Farnese Rome, Palazzo Farnese, Carracci Gallery. On one side of the entrance door stands a copy of the famous Antinous-Farnese, in the place occupied by the original statue before it was taken to Naples to the Royal Borbonic Museum (Reale Museo Borbonico), now National Archaeological Museum. The 18th century's statuary decoration has been recreated in the years 1970's by casts of the original marbles which once adorned the premises

Tertullian of Carthage (c.160-c.240): Attacks Antinous in four different books written between 197 & 207.

Ad Marc.Bk I, ch. 18 - (trl. Holmes) "As for the rest, if man shall be thus able to devise a god,--as Romulus did Consus, and Tatius Cloacina, and Hostilius Fear, and Metellus Alburnus, and a certain authority [sc. Hadrian] some time since Antinous,--the same accomplishment may be allowed to others."

Apologeticus (c.197) ch. 13 - (trl. Thelwall) "When you make an infamous court page (de paedagogiis aulicis) a god of the sacred synod."

De Corona Militis ch. 13 - "Will there be any dispute as to the cause of crown-wearing, which contests in the games in their turn supply, and which, both as sacred to the gods and in honour of the dead, their own reason at once condemns? It only remains, that the Olympian Jupiter, and the Nemean Hercules, and the wretched little Archemorus, and the hapless (infelix) Antinous, should be crowned in a Christian, that he himself may become a spectacle disgusting to behold."

Ad Nationes (c.217) Bk II, ch. 10 - "After so many examples and eminent names among you, who might not have been declared divine? Who, in fact, ever raised a question as to his divinity against Antinous? Was even Ganymede more grateful and dear than he to (the supreme god) who loved him? According to you, heaven is open to the dead. You prepare a way from Hades to the stars. Prostitutes mount it in all directions, so that you must not suppose that you are conferring a great distinction upon your kings."

The Belvedere Antinous St. Petersburg, Peterhof, Grand Cascade. Copy 1800 by the sculptor Fedor Gordeevich Gordeev (1744-1810) and the founder Vasily Petrovich Ekimov (1758-1837).

The Belvedere Antinous Madrid, Prado, Room 80. Inv.N. E00181. Hight 75 cm. Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) brought this magnificent bronze bust from Italy, where he stayed from 1648 to 1651, entrusted by King Philip IV with the purchase of sculptures and paintings to decorare the Alcázar. The palace was completely destroyed by a fire in 1734 and with it, lots of works of art that could not be evacuated on time. This bust escaped the disaster.

Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria (c.295-c.373):

Contra Gentes (c.350) Part I, ch. 9 - ". . . and in our own time Antinous, favourite of Hadrian, Emperor of the Romans, whom, although men know he was a mere man, and not a respectable man, but on the contrary, full of licentiousness, yet they worship for fear of him that enjoined it. For Hadrian having come to sojourn in the land of Egypt, when Antinous the minister of his pleasure died, ordered him to be worshipped; being indeed himself in love with the youth even after his death, but for all that offering a convincing exposure of himself, and a proof against all idolatry, that it was discovered among men for no other reason than by reason of the lust of them that imagined it."

Apologia Contra Arianos Part III, ch. 5, §230 - (trl. Parker, 1713; quoted in Lambert p. 7 ¶) "And such a one is the new God Antinous, that was the Emperor Hadrian's minion and the slave of his unlawful pleasures; a wretch, whom those that worshipped in obedience to the Emperor's command, and for fear of his vengeance, knew and confessed to be a man, and not a good or deserving man neither, but a sordid and loathsome instrument of his master's lust. This shameless and scandalous boy died in Egypt when the court was there; and forthwith his Imperial Majesty issued out an order or edict strictly requiring and commanding his loving subjects to acknowledge his departed page a deity and to pay him his quota of divine reverences and honours as such: a resolution and act which did more effectually publish and testify to the world how entirely the Emperor's unnatural passion survived the foul object of it; and how much his master was devoted to his memory, than it recorded his own crime and condemnation, immortalised his infamy and shame, and bequeathed to mankind a lasting and notorious specimen of the true origin and extraction of all idolatry."

¶ Lambert p. 7 n.10 (quoting Apol. Contra Arianos but attributing it to Contra Gentes I.9)

Antinous Mondragone at the Louvre Museum

History of the Church [Hist. Eccl.] (c.310) Bk 4, ch.8 - §2 quoting Hegesippus (Memoirs c.180 - lost): "Among whom [sc. idols] is also Antinoüs, a slave (doulos) of the Emperor Hadrian, in whose honor are celebrated also the Antinoian games, which were instituted in our day. For he [Hadrian] also founded a city named after Antinoüs, and appointed prophets." §3: "At the same time also Justin, a genuine lover of the true philosophy, was still continuing to busy himself with Greek literature. He indicates this time in the Apology which he addressed to Antonine, where he writes as follows: 'We do not think it out of place to mention here Antinoüs also, who lived in our day, and whom all were driven by fear to worship as a god, although they knew who he was and whence he came'."

Known as the "Marlborough Gem", after a previous owner, the House of Marlborough, who kept it from 1761 to 1875. The gem is mentioned for the first time in Venice in 1740, in the collection of A.M. Zanetti [1689-1767]. It can be traced as early as 1720, but it is not known in which hands it was at that time, or where it was found.

Antinous Mondragone at the Louvre Museum

Socrates Scholasticus, Church Historian (born c. 380):

Church History (c. 439) Bk 3, ch. 23: "The inhabitants of Cyzicus declared Hadrian to be the thirteenth god; and Adrian himself deified his own catamite Antinoüs."

Castor and Pollux (Prado). The lefthand figure was originally headless but was restored in the 17th century, the heyday of interpretive restorations, by Ippolito Buzzi, when the sculpture was in the collection of Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, using a Hadrianic-era (ca. 130) bust of Antinous of the Apollo-Antinous type from another statue. The identification of the figures inspired many choices of male pairs during the 17th and 18th centuries. During the 19th century, it became known as "Antinous and Hadrian's genius", to get over the problem of their both being youths, whereas ahistorically it was an important feature of Antinous' relationship with Hadrian that Antinous was a youthful eromenos and Hadrian an elder erastes. Alternatively "Antinous and a sacrificial daemon" was suggested, in reference to the myth that Antinous had killed himself as a sacrifice to lengthen Hadrian's life), or simply as Antinous and Hadrian pledging their fidelity to one another.

Capitoline Antinous, Capitoline Museums, from the Villa Adriana

(St) Epiphanius, Bishop of Constantia (Salamis) (c.315-403) attacks Antinous in three separate books.

Antinous As Bacchus

(St) Jerome (c.347-419/420) attacks Antinous in four separate books, usually referring to him in Latin as in deliciis (= Gk paidika) (darling, favourite; alluring or delightful boy).

Interpr. Chronicon Eusebius (c.380/1) (based on ed. Roger Pearse):

CCXXIV Olympias Romanorum XII, Hadrianus, regnavit annis XXI - in 224th Olympiad [under regnal year 2 (= 118CE)] "Hadrian was most erudite in both languages, but also he was not self-controlled enough in his desire for boys" (Hadrianus eruditissimus fuit in utraque lingua, sed in puerorum amore parum continens fuit.);

CCXXVII Olympias - in 227th Olympiad [under regnal year 13 (= 129CE, recte 130)] "Antinous, a boy of surpassingly exceptional beauty, dies in Egypt. After Hadrian attentively carries out his funeral rites (diligenter sepeliens) [variant vehementer deperiens i.e., grieved vehemently] - for the boy had been a favourite of his [literally, had been treated as a darling] -, he declares him to be among the gods; a city was also named after him." (Antinous puer egregius eximiae pulchritudinis, in Aegypto moritur, quem Hadrianus diligenter sepeliens, --nam in deliciis habuerat-- in deos refert, ex cujus nomine etiam urbs appellata est.)

Adversus Jovinianum (393) Bk II, ch. 7 - "And to make us understand what sort of gods Egypt always welcomed, one of their cities was recently called Antinous after the love of Hadrian's heart."

De Viris Illustribus ch. 22 - "Hegesippus [d.180 - see above under Eusebius] who lived at a period not far from the Apostolic age, writing a History of all ecclesiastical events, from the passion of our Lord down to his own period. [. . .] arguing against idols, he wrote [. . .] showing from what error they had first arisen, and this work indicates in what age he flourished. He says, 'They built monuments and temples to their dead as we see up to the present day, such as the one to Antinous, servant to the Emperor Hadrian, in whose honour also games were celebrated, and a city founded bearing his name, and a temple with priests established.' It is written moreover that the Emperor Hadrian was enamoured of Antinous." (Tumulos mortuis templaque fecerunt, sicut usque hodie videmus: e quibus est et Antinous servus Hadriani Caesaris, cui et gymnicus agon exercetur apud Antinoum civitatem, quam ex ejus nomine condidit, et statuit prophetas in templo. Antinoum autem in deliciis habuisse Caesar Hadrianus scribitur.)

Comm. Isaiah 2 - equates Antinous with a public concubine (Lambert p. 193).

Versailles, Castle. 18th century marble bust, formerly in the Royal Collections, exhibited today near the "Ambassadors’ Staircase".

Prudentius (348-post 405):Contra Symmachum (c.384) I.267-277: Lambert on p. 7 n.8 writes: "Who would not be struck by Prudentius' scathing image of Antinous nestling in Hadrian's 'purple clad bosom' and 'being robbed of his manhood' (illum purporeo in gremio spoliatum sorte virili) or lolling on a couch 'listening to the prayers in the temples with his husband'?" (I.273-7) Lambert comments ( p. 67 n.33): that the above passage is "more a euphemism for seduction than castration" .

Capitoline Antinous, Capitoline Museums, from the Villa Adriana

London, Sir John Soane’s Museum, Inv. N° DS.213 (V.855). Antique cameo.

Suidas Lexicon (c.1000) (ed. Bernhardy 1853) gives Antinous as example of paidika, defined as "an agreeable boy but usually one of lascivious and foul affections".

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Cabinet des médailles. Sardony cameo, antique.

Berlin, Altes Museum, Inv. N° R. 57, displayed in Hall 30. Portrait of Antinous at age 13 with myrtle wreath. Acquired in 1878 in Cairo

Berlin, Altes Museum, Inv. N° R. 57, displayed in Hall 30. Portrait of Antinous at age 13 with myrtle wreath. Acquired in 1878 in Cairo

Castor and Pollux (Prado). The lefthand figure was originally headless but was restored in the 17th century, the heyday of interpretive restorations, by Ippolito Buzzi, when the sculpture was in the collection of Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, using a Hadrianic-era (ca. 130) bust of Antinous of the Apollo-Antinous type from another statue. The identification of the figures inspired many choices of male pairs during the 17th and 18th centuries. During the 19th century, it became known as "Antinous and Hadrian's genius", to get over the problem of their both being youths, whereas ahistorically it was an important feature of Antinous' relationship with Hadrian that Antinous was a youthful eromenos and Hadrian an elder erastes. Alternatively "Antinous and a sacrificial daemon" was suggested, in reference to the myth that Antinous had killed himself as a sacrifice to lengthen Hadrian's life), or simply as Antinous and Hadrian pledging their fidelity to one another.

Antinous from Delphi

Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazional, Inv. N° 6030, exhibited in Hall VIII. Exact origin unknown. Called the "Antinous Farnese," after the name of its first owner

Antinous from Delphi

Cameo representing the Antinous Braschi, signed by Barthali, ca. 1860.

Berlin, Altes Museum, Inv. N° R. 56, displayed in Hall 30.Presently (2005) lent to an exhibition held in Tokyo and Kobe. Antinous as Dionysos. Origin unknown. In the 16th Century, it was the property of Giovanni Grimani. Acquired 1859 by the Altes Museum.

Berlin, Altes Museum, Inv. N° R. 56, displayed in Hall 30.Presently (2005) lent to an exhibition held in Tokyo and Kobe. Antinous as Dionysos. Origin unknown. In the 16th Century, it was the property of Giovanni Grimani. Acquired 1859 by the Altes Museum.

Castor and Pollux (Prado). The lefthand figure was originally headless but was restored in the 17th century, the heyday of interpretive restorations, by Ippolito Buzzi, when the sculpture was in the collection of Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, using a Hadrianic-era (ca. 130) bust of Antinous of the Apollo-Antinous type from another statue. The identification of the figures inspired many choices of male pairs during the 17th and 18th centuries. During the 19th century, it became known as "Antinous and Hadrian's genius", to get over the problem of their both being youths, whereas ahistorically it was an important feature of Antinous' relationship with Hadrian that Antinous was a youthful eromenos and Hadrian an elder erastes. Alternatively "Antinous and a sacrificial daemon" was suggested, in reference to the myth that Antinous had killed himself as a sacrifice to lengthen Hadrian's life), or simply as Antinous and Hadrian pledging their fidelity to one another.

Head (the bust is modern), Antikensammlung Berlin. A good friend owned a 18th century copy of this bust.

Head (the bust is modern), Antikensammlung Berlin

Head (the bust is modern), Antikensammlung Berlin

Antinous As Bacchus

Large Cameo, showing the Antinous Braschi, ca. 1850-1860.

Victorian Cameo of Antinous As Bacchus

Antinous Ecouen, from Villa Adriana at Tivoli

Antinous Ecouen, from Villa Adriana at Tivoli

Antinous Ecouen, from Villa Adriana at Tivoli

Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Inv. N° 6314, displayed in Room XXIX.Antinoos als Bacchus. Traced in the Farnese collection since 1644 and undisputed portrait of Antinous for a long time.

Rome, Villa Albani (private collection). Found in 1735 in the Villa Hadriana. Immediately bought by the Cardinal Alessandro Albani, hence referred to as “Albani Relief” as of the end of the 18th century. Although the Villa Albani belongs to House of Torlonia since 1866, this relief is still kept at exactly the same place where the Cardinal had it displayed in 1760/62.

Rome, Villa Albani (private collection). Inv. N° 1013. Relief of unknown provenance, restored arbitrarily towards the middle of the 18th century with a contemporary head of Antinous

Rome, Banca d'Italia, Via Nazionale, exhibited in the inner courtyard. Antinous-Dionysos. Found in 1886 at its present location, during the construction of the building. (1st photo: original position; 2nd photo: present location) «Questo ritratto può riguardarsi come uno di quelli che le espressero più al vero» (Carlo Ludovico Visconti, 1886)

Rome, Chigi Chappel in S.M. del Popolo, Jonas, Marble statue by Lorenzetto - evidently inspired by the head of the Antinous Farnese in Naples, Mid-16th Century.

Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptothek, Inv. N° 1960, exhibited in the "Festsal." Found ca. 1700 in the Garden of the now-demolished Villa Casali in Rome. Called the "Antinous Casali," after its origin

The Antinoopolitan Gay Lovers

Cairo, Egyptian Museum. Inv. No CG 33267, exhibited in Room 14, in the First Floor. Funerary portrait found at Antinoopolis or Antinoe the city founded by Hadrian on the site of Hir-wer where Antinous died , This double portrait was probably found by Albert Jean Gayet, who unearthed numerous painted portraits in the area from 1896 to 1911. Exhibited in the "Exposition Universelle" of 1900 in Paris, it is a double portrait, with a diameter of 61 cm, and dated between 130-140 AD, referred to as the Tondo of the Brothers. Some scholars now think that the two men depicted were lovers. But of even more significance are the small images of Greco-Egyptian gods placed above their shoulders. The older man is guarded by Hermanubis, a god of the underworld; the younger is watched over by a deity at first identified as Harpocrates, but Dr. Klaus Parlasca in "Mumienporträts und verwandte Denkmäler" (1969) identified it first as Osiris Antinous, the patron god of Antinoopolis. This would make the Tondo the only painting of Antinous to have survived, and the only image of two probable members of his cult.

Dr. Klaus Parlasca identified it first as Osiris Antinous, the patron god of Antinoopolis.

Phew! A history book. How long did it take you to write this post?

ReplyDeleteDating for everyone is here: ❤❤❤ Link 1 ❤❤❤

DeleteDirect sexchat: ❤❤❤ Link 2 ❤❤❤

Mg .

Hi cieldequimper it tuck a day to upload all the photo's and two days to research and write the post but it was fun and I loved it now I'm working on the story of Cupid and Psyche explored thru decorative arts for valentines day. Have a great weekend!!!!

ReplyDeleteReally great- Antinous is my favorite personage of the classical world. I would love to have been him. Although he died young, his life with Hadrian had to have been amazing.

ReplyDeleteall these ancient stories seem so glorious to me

ReplyDeleteDating for everyone is here: ❤❤❤ Link 1 ❤❤❤

ReplyDeleteDirect sexchat: ❤❤❤ Link 2 ❤❤❤

yw .